This article is part two of the Malt Whisky and Place series. Please refer to part one if you haven’t yet read it yet.

Dr Nicholas Morgan

First up to speak was Dr Nicholas Morgan, along with our first dram of the night, Lagavulin new make spirit. Thanks to Ernst J. Scheiner from Gateway to Distilleries for the picture of new make running from the stills at Lagavulin. The sample was principally for us to get our noses in gear (to get our organoleptic senses started, or so we were told) and it came with a big health warning that we may not want to drink it (who’s he kidding?!) as it’s new spirit that comes directly from the stills. It was only around a month old and not matured in any way in wood, and came in at a hefty 68.5%. For me a fantastic deliverance back to the Lagavulin Distillery where I first tried this as part of a warehouse tour in 2012. It’s wonderfully fruity and powerful.

First up to speak was Dr Nicholas Morgan, along with our first dram of the night, Lagavulin new make spirit. Thanks to Ernst J. Scheiner from Gateway to Distilleries for the picture of new make running from the stills at Lagavulin. The sample was principally for us to get our noses in gear (to get our organoleptic senses started, or so we were told) and it came with a big health warning that we may not want to drink it (who’s he kidding?!) as it’s new spirit that comes directly from the stills. It was only around a month old and not matured in any way in wood, and came in at a hefty 68.5%. For me a fantastic deliverance back to the Lagavulin Distillery where I first tried this as part of a warehouse tour in 2012. It’s wonderfully fruity and powerful.

Nick quickly introduced us to Diageo (for those not already acquainted) and tried to put some perspective onto the size of the whisky industry and their place within it as the largest alcoholic beverage producer in the world, to which whisky is the most important part of their business in terms of annual profits and growth. However comparing the total output of the Scotch whisky industry (80m-90m cases a year) against the rest of the world, it’s actually a tiny industry. Nick went on to put some further perspective on the industry by mentioning just what a large part of it is the blended whisky market. This is important as the blended whisky market drives the single malt markets which make up the constituent parts to the various brands. He argues that the creation of so many great quality malt whiskies has been driven by the needs of the blenders.

With terroir Nick has 3 main things in mind, people, process (including raw materials) and place. He broke down a few points for us:

Water. The availability of large quantities of water is critical to the process of making whisky. You need water as a constituent part of whisky but you also need huge amounts of water for other parts of the process. Most distilleries will have two sources of water, and Diageo go to great lengths via legal departments to protect water and to prevent pollution by such things as Nitrates which would produce ‘bad’ water. However, as long as the water is ‘good’ then he says that any water will do, he suggests that it has even less effect on flavour (in fact no effect at all) than the chart above suggests. Distilleries were set up originally near good sources of water for the very fact that so much is needed for production, so in that respect the ‘place’ as such is out of need for water supply, rather than for the flavour aspect of the location (as maybe suggested in marketing materials).

Barley. It would be great to say that Scotch whisky is made from Scottish barley. However the fact of the matter is that there just isn’t enough barley available from Scotland, and so Diageo gets most of its barley from East Anglia. And if there’s not enough available from East Anglia they’ll basically get it from wherever they need to to be able to carry on production. We are reminded that 100 years ago distilleries on Islay were getting their barley from such places as Canada and Australia. Nick says all they’re interested in is good barley (wherever that may be from) as all they need it to do is produce lots of alcoholic yield. If it is malted and peated then it has a huge effect on flavour, but if it’s not peated he intimates that there’s a minimal effect on the final flavour.

Peat. He agrees this is hugely important, and helps define much of the Islay whiskies that are produced on the island today. 100 years ago it would have defined the flavour of almost all single malt whisky made in Scotland as it was the only way to dry the malt that was produced.

Yeast. Basically has no effect on flavour in his opinion, it is something that enables the fermentation process to happen. He agrees the fermentation process is a huge point of flavour creation, but says it’s not about the yeast which just fulfils a function, he says there’s other “stuff” that goes on to create the flavours here (no further explanation).

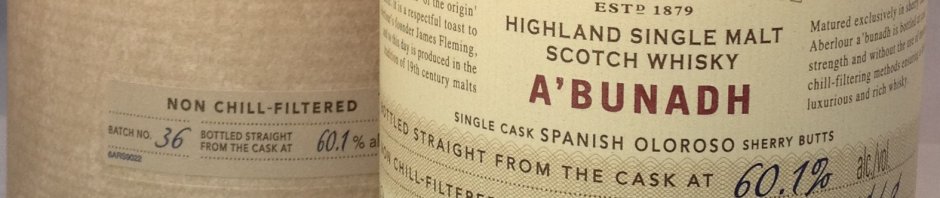

Time and Wood. Scotch whisky is matured in oak casks for a minimum of 3 years in Scotland, but the wood for the casks very rarely comes from oak grown in Scotland, it mostly comes from the US in the form of Bourbon casks, or comes from Spain where it was probably used for sherry casks. There is often confusion about wood, however the quality of the wood (i.e. the activity you get from a cask by which we mean the way in which the liquid interacts with the wood) is what’s absolutely critical.

Terroir. Nick describes the use of terroir when applied to whisky as a brilliant marketing concept for the growth and development of premium single malts. He suggests that its first use when applied to whisky was when his previous colleagues introduced the Classic Malts selection in 1987-1988. He goes on to say that his colleague was previously a wine guy and wanted to tap into the wine terroir market with whisky to be able to grow the category in valuable markets such as France, Spain and Italy who understood those concepts, but where bulk blended whisky at that point had been seen as a rather low quality product with a low grade reputation. He wanted to play to the quality image that terroir tended to have in consumers’ minds. So in that respect Nick is intimating that terroir is completely a marketing gimmick, and goes on to say that terroir in so far as whisky is actually concerned should be forgotten and that distillers from 50 years ago would have said you were ‘nuts’.

Nick now tells us a story about Peter Mackie who was the owner of White Horse Distillers which once owned Lagavulin Distillery, and who was an Islay whisky making maverick. Mackie was convinced that science was the way to understand whisky and to tame it, and as such set up the first scientific laboratory to research into whisky which was based in Hazelburn in Campbeltown, and later moved to Glasgow. He set about changing Hazelburn whisky to remove disliked taste notes and claimed he had turned it into a fine whisky equal to the best highland whiskies. With this claim he is stating that it was the process that could (and was) changed to create different whiskies, and therefore is not related to place. However as much Mackie tried to push Hazelburn whisky and say it was now like a Glenlivet, it never really was.

Peter Mackie was also a distributor for Laphroaig, but in 1907 that right of distribution was taken away from him. Therefore in 1908 he decided he’d build a replica of Laphroaig Distillery inside the grounds of Lagavulin, known as Malt Mill Distillery. At that point Mackie already thought he knew enough about Laphroaig’s processes to be able to reproduce it. He was able to tap into the water supply of Laphroaig and he had the barley peated to a Laphroaig specification, etc. However, the whisky that was produced never matched the Laphroaig character even though it was made less than half a mile away.

In the last story from Nick he talks about Brora. In 1968 there was a drought on Islay. At that point the Distillers Company Limited (DCL) had 3 distilleries in production on the island (Lagavulin, Caol Ila and Port Ellen), all working overtime to produce as much whisky as possible for blends, and with expanding US markets it was critical that there was enough production to keep the blenders well supplied. In the face of what was nearly a years’ worth of lost production due to the drought, DCL decided they would simply make Lagavulin somewhere else, and the distillery they chose was a distillery located in the north east of Scotland, in the village of Brora. The distillery was called Clynelish and had been closed in 1968 after being rebuilt into a new facility on an adjacent field. The new facility was then called Clynelish, and the old distillery site, now pressed back into use, was renamed to Brora.

The job of creating a new Lagavulin style whisky at Brora was taken seriously. Malt was produced in Glasgow and in Glen Ord to the specification that was used in Lagavulin. That malt was then shipped to Lagavulin to be tested out on their stills to ensure it created proper Lagavulin style whisky, which it did. Brora then went into production using this malt, and a year later meeting minutes from the Company state that Brora was regarded as ‘indistinguishable from the output from the three Islay distilleries’. Production carried on for some time, and once the Islay distilleries had recovered from the drought and started to increase their production again the facility at Brora stopped producing and the experiment to produce Islay whisky on the main land was never repeated. Nowadays although Brora is often highly regarded, it’s accepted that it never tasted like the Islay distilleries it was trying to replicate even though it was peated.

These stories all highlight situations where people believed they could replicate the style of other whiskies using all their knowledge of them in different locations where they all failed.

Nick states again that he doesn’t believe in terroir, so poses the question of what is it then that defines the character of single malt whisky? He believes it’s the precise location where a distillery resides. He believes that no amount of science can replicate the factors that come together to form a distillery in a particular location, in fact he states that no amount of scientific investigation has yet answered the conundrum as to why this is. He says that with whatever we know now, we could still not build a new Laphroaig at Lagavulin, it’s simply not possible. He says the precise location is what is crucial in defining the flavour of the particular whisky.

He sums up by saying that terroir in the context of wine simply can’t apply to whisky because there are so many different variables that are not associated with the place that come in to play when you make whisky.

Please click here for part three of this article series to read the thoughts of Jim McEwan.

I agree so far, I’ve never thought of malt whisky as being a ‘terroir’ thing, but I don’t think it detracts from it in any way. I’ll reserve judgement though – great stuff so far!

LikeLike

Thanks Gareth, very kind… and I completely agree with your terroir thoughts. 🙂

LikeLike