This article is part three of the Malt Whisky and Place series. Please refer to parts one and two if you haven’t yet read them yet.

Jim McEwan

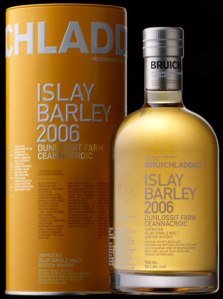

Next to speak was Jim McEwan from Bruichladdich (and previously Bowmore amongst others), this time with a dram of Bruichladdich Islay Barley 2006 for us all. Bruichladdich is well known for strongly being identified with ‘place’, and Jim quickly points out on a map where the island of Islay is located and where the distillery is on the island, showing that if you go west from Islay you come to Newfoundland, meaning that most days you get the wind and the salty rain coming from the west coast.

Next to speak was Jim McEwan from Bruichladdich (and previously Bowmore amongst others), this time with a dram of Bruichladdich Islay Barley 2006 for us all. Bruichladdich is well known for strongly being identified with ‘place’, and Jim quickly points out on a map where the island of Islay is located and where the distillery is on the island, showing that if you go west from Islay you come to Newfoundland, meaning that most days you get the wind and the salty rain coming from the west coast.

Jim recounts how as a young boy he wanted to become a cooper, and how he studied for 6 years to become one. He knows casks inside and out and has spent most of his life nosing them and the whisky that come out of them. He learnt how to malt at Bowmore (at the 4 maltings there), his grandfather was also maltman there. He learnt how to mash and how to distil, and soon became Cellar Master there looking after the storage and quality of the casks. Jim regales us with anecdotes of past times where he would syphon off what is now known as Black Bowmore from 1964 into hot water bottles, which tasted great, if not a little rubbery.

Jim then trained for 3 years as a blender in Glasgow, and was a blend manager for 8 years for Morrison Bowmore Distillers. He then came back to Islay as manager of Bowmore distillery before then going around the world teaching about whisky.

After a while Jim then came back to Islay once more to start getting Bruichladdich back up and running again, getting equipment from 1881 back into working order, which is still used today.

Bruichladdich is traditionally not a peated whisky, but to quell critics they also then produced a peated whisky, Port Charlotte, followed by a super heavily peated whisky, Octomore.

Whisky had not been made on Islay with Islay grown barley since the outbreak of war in 1939, since which time large amounts of the barley has come from East Anglia (as mentioned earlier). With this in mind Jim was determined to see if terroir existed and wanted to make Islay whisky with Islay barley, which he is convinced must be slightly different. He compares warm sheltered East Anglian barley to the barley grown on the wilds of Islay getting bashed with the Atlantic wind and the salty rain from the vast sea crossing between the island and Newfoundland and says there must be a difference.

Whisky had not been made on Islay with Islay grown barley since the outbreak of war in 1939, since which time large amounts of the barley has come from East Anglia (as mentioned earlier). With this in mind Jim was determined to see if terroir existed and wanted to make Islay whisky with Islay barley, which he is convinced must be slightly different. He compares warm sheltered East Anglian barley to the barley grown on the wilds of Islay getting bashed with the Atlantic wind and the salty rain from the vast sea crossing between the island and Newfoundland and says there must be a difference.

Jim agrees that terroir is a ‘French thing for wine’, but does believe in its general meaning. He says that terroir is about the island, about the people and about social responsibility.

Water. Jim agrees that water has virtually no flavour input to whisky. A lot of it is needed for the process, but that the end product doesn’t take much flavour from it. However he makes a good point that when bottling a whisky, which Bruichladdich do on the island, they take pure clear spring water to reduce the alcoholic strength down to 46%. He is clear that this part of the process does indeed add flavour to the product; water that has come from a spring in the hills, through old rock and through wild flowers and mosses is soft and contributes to the gentle sweet taste, and is of course quite different to water that has been through city pipes or reverse osmosis on the mainland. Jim believes that this part is important and contributes to the terroir of their malt whisky.

Barley. Islay is the most fertile of all the islands of Scotland, and therefore very good for growing barley. The rain super saturates the ground with salt as it comes over the sea. Jim talks about the destitution of farmers on the island in the wake of Mad Cow disease and the falling prices for sheep etc. He is keen that the social responsibility of Bruichladdich helps to get these farmers going again by encouraging them to grow barley once more on Islay for the first time in many years. This meant investment and new machinery which was a worry for the local farmers but by sticking together they now produce around 1000 tonnes a year which produces Bruichladdich’s Islay Barley whisky. Jim says that with all his 50 years’ worth of experience the Islay barley spirit shows a clear difference on the nose from barley that was grown elsewhere. He says that if anyone noses whisky made from 15 different locations around Scotland you will find a subtle difference to them all. Jim goes as far as to say that even Islay barley has variations. Barley grown at Kilchoman, which is sandy soil, and barley grown at Cruach, which has peaty soil, shows a difference on the new spirit. He thinks it would be difficult to still find those differences 15 years later after maturation in the cask, but at the point of distillation he is sure there is a difference.

Barley. Islay is the most fertile of all the islands of Scotland, and therefore very good for growing barley. The rain super saturates the ground with salt as it comes over the sea. Jim talks about the destitution of farmers on the island in the wake of Mad Cow disease and the falling prices for sheep etc. He is keen that the social responsibility of Bruichladdich helps to get these farmers going again by encouraging them to grow barley once more on Islay for the first time in many years. This meant investment and new machinery which was a worry for the local farmers but by sticking together they now produce around 1000 tonnes a year which produces Bruichladdich’s Islay Barley whisky. Jim says that with all his 50 years’ worth of experience the Islay barley spirit shows a clear difference on the nose from barley that was grown elsewhere. He says that if anyone noses whisky made from 15 different locations around Scotland you will find a subtle difference to them all. Jim goes as far as to say that even Islay barley has variations. Barley grown at Kilchoman, which is sandy soil, and barley grown at Cruach, which has peaty soil, shows a difference on the new spirit. He thinks it would be difficult to still find those differences 15 years later after maturation in the cask, but at the point of distillation he is sure there is a difference.

Jim goes on to discuss quality oak wood casks for giving flavour to whisky. Bruichladdich uses lots of wine casks (amongst others), and he is obviously very passionate about experimenting with the best casks he can get his hands on and is keen to point out that he doesn’t use any caramel colouring which he suggests must add extra unnatural flavour to whisky.

Jim thinks that people are part of terroir, and continues to say that Bruichladdich uses lots of highly skilled people who put their heart and soul into the whisky they produce.

“I believe completely in terroir 100%. I believe in the water, I believe in the barley, I believe in the casks.” Says Jim. However he does concede that marketing people have overdone it.

Thanks to Gerda Reuss, Roddy Mackay and Carl Reavey for the use of their pictures.

Please click here for part four of this article series to read the thoughts of Georgie Crawford and to see the summary.

Very interesting article – well done! I guess it shouldn’t be a tremendous surprise to learn that fermentation schedules, still volume/capacity, temperature and other steps in the distillation process, as well as the aging and cask selection, contribute more to the final product than simply the location.

LikeLike

Hi Eric, thanks for your comments! I totally agree, it’s not exactly a tremendous surprise really is it? 🙂

LikeLike